Saccaka asked the Blessed One: “Has there never arisen in Master Gotama a

feeling so pleasant that it could invade his mind and remain? Has there never

arisen in Master Gotama a feeling so painful that it could invade his mind and

remain?”

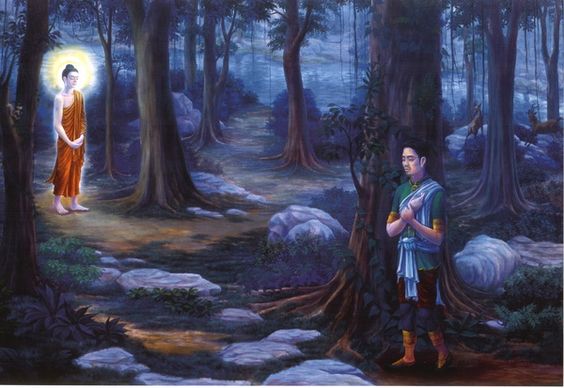

“Why not,

Aggivessana? Here, Aggivessana, before my enlightenment, while I was still only

an unenlightened bodhisatta, I thought: ‘Household life is crowded and dusty;

life gone forth is wide open. It is not easy, while living in a home, to lead

the holy life utterly perfect and pure as a polished shell. Suppose I shave off

my hair and beard, put on the ochre robe, and go forth from the home life into

homelessness.’

“Later, while still

young, a black-haired young man endowed with the blessing of youth, in the

prime of life …And I sat down there thinking: ‘This will serve for striving.’

“Now these three

similes occurred to me spontaneously, never heard before. Suppose there were a

wet sappy piece of wood lying in water, and a man came with an upper

fire-stick, thinking: ‘I shall light a fire, I shall produce heat.’ What do you

think, Aggivessana? Could the man light a fire and produce heat by taking the

upper firestick and rubbing it against the wet sappy piece of wood lying in the

water?”

“No, Master Gotama.

Why not? Because it is a wet sappy piece of wood, and it is lying in water.

Eventually the man would reap only weariness and disappointment.”

“So too,

Aggivessana, as to those ascetics and brahmins who still do not live bodily

withdrawn from sensual pleasures, and whose sensual desire, affection,

infatuation, thirst, and fever for sensual pleasures has not been fully abandoned

and suppressed internally, even if those good ascetics and brahmins feel

painful, racking, piercing feelings due to exertion, they are incapable of

knowledge and vision and supreme enlightenment; and even if those good ascetics

and brahmins do not feel painful, racking, piercing feelings due to exertion,

they are incapable of knowledge and vision and supreme enlightenment. This was

the first simile that occurred to me spontaneously, never heard before.

“Again, Aggivessana,

a second simile occurred to me spontaneously, never heard before. Suppose there

were a wet sappy piece of wood lying on dry land far from water, and a man came

with an upper fire-stick, thinking: ‘I shall light a fire, I shall produce

heat.’ What do you think, Aggivessana? Could the man light a fire and produce

heat by taking the upper fire-stick and rubbing it against the wet sappy piece

of wood lying on dry land far from water?”

“No, Master Gotama.

Why not? Because it is a wet sappy piece of wood, even though it is lying on

dry land far from water. Eventually the man would reap only weariness and

disappointment.”

“So too,

Aggivessana, as to those ascetics and brahmins who live bodily withdrawn from

sensual pleasures, but whose sensual desire, affection, infatuation, thirst, and

fever for sensual pleasures has not been fully abandoned and suppressed

internally, even if those good ascetics and brahmins feel painful, racking,

piercing feelings due to exertion, they are incapable of knowledge and vision

and supreme enlightenment; and even if those good ascetics and brahmins do not

feel painful, racking, piercing feelings due to exertion, they are incapable of

knowledge and vision and supreme enlightenment. This was the second simile that

occurred to me spontaneously, never heard before.

“Again, Aggivessana, a third simile occurred to me

spontaneously, never heard before. Suppose there were a dry sapless piece of

wood lying on dry land far from water, and a man came with an upper fire-stick,

thinking: ‘I shall light a fire, I shall produce heat.’ What do you think,

Aggivessana? Could the man light a fire and produce heat by rubbing it against

the dry sapless piece of wood lying on dry land far from water?”

“Yes, Master Gotama.

Why so? Because it is a dry sapless piece of wood, and it is lying on dry land

far from water.”

“So too, Aggivessana, as to those ascetics and brahmins who

live bodily withdrawn from sensual pleasures, and whose sensual desire,

affection, infatuation, thirst, and fever for sensual pleasures has been fully

abandoned and suppressed internally, even if those good ascetics and brahmins

feel painful, racking, piercing feelings due to exertion, they are capable of

knowledge and vision and supreme enlightenment; and even if those good ascetics

and brahmins do not feel painful, racking, piercing feelings due to exertion,

they are capable of knowledge and vision and supreme enlightenment.16 This was

the third simile that occurred to me spontaneously, never heard before. These

are the three similes that occurred to me spontaneously, never heard before.

“I thought: ‘Suppose,

with my teeth clenched and my tongue pressed against the roof of my mouth, I

beat down, constrain, and crush mind with mind.’ So, with my teeth clenched and

my tongue pressed against the roof of my mouth, I beat down, constrained, and

crushed mind with mind. While I did so, sweat ran from my armpits. Just as a

strong man might seize a weaker man by the head or shoulders and beat him down,

constrain him, and crush him, so too, with my teeth clenched and my tongue

pressed against the roof of my mouth, I beat down, constrained, and crushed

mind with mind, and sweat ran from my armpits. But although tireless energy was

aroused in me and unremitting mindfulness was established, my body was

overwrought and strained because I was exhausted by the painful striving. But

such painful feeling that arose in me did not invade my mind and remain

“I thought: ‘Suppose

I practice the breathless meditation.’ So I stopped the in-breaths and

out-breaths through my mouth and nose. While I did so, there was a loud sound

of winds coming out from my ear holes. Just as there is a loud sound when a

smith’s bellows are blown, so too, while I stopped the in-breaths and

out-breaths through my nose and ears, there was a loud sound of winds coming

out from my ear holes. But although tireless energy was aroused in me and

unremitting mindfulness was established, my body was overwrought and strained

because I was exhausted by the painful striving. But such painful feeling that arose

in me did not invade my mind and remain.

“I thought: ‘Suppose

I practice further the breathless meditation.’ So I stopped the in-breaths and

out-breaths through my mouth, nose, and ears. While I did so, violent winds cut

through my head. Just as if a strong man were pressing against my head with the

tip of a sharp sword, so too, while I stopped the in-breaths and out-breaths

through my mouth, nose, and ears, violent winds cut through my head. But

although tireless energy was aroused in me and unremitting mindfulness was

established, my body was overwrought and strained because I was exhausted by

the painful striving. But such painful feeling that arose in me did not invade

my mind and remain.

“I thought: ‘Suppose

I practice further the breathless meditation.’ So I stopped the in-breaths and

out-breaths through my mouth, nose, and ears. While I did so, there were

violent pains in my head. Just as if a strong man were tightening a tough

leather strap around my head as a headband, so too, while I stopped the

in-breaths and outbreaths through my mouth, nose, and ears, there were violent

pains in my head. But although tireless energy was aroused in me and

unremitting mindfulness was established, my body was overwrought and strained

because I was exhausted by the painful striving. But such painful feeling that

arose in me did not invade my mind and remain.

“I thought: ‘Suppose

I practice further the breathless meditation.’ So I stopped the in-breaths and

out-breaths through my mouth, nose, and ears. While I did so, violent winds

carved up my belly. Just as if a skilled butcher or his apprentice were to

carve up an ox’s belly with a sharp butcher’s knife, so too, while I stopped

the in-breaths and outbreaths through my mouth, nose, and ears, violent winds

carved up my belly. But although tireless energy was aroused in me and

unremitting mindfulness was established, my body was overwrought and strained

because I was exhausted by the painful striving. But such painful feeling that

arose in me did not invade my mind and remain.

“I thought: ‘Suppose

I practice further the breathless meditation.’ So I stopped the in-breaths and

out-breaths through my mouth, nose, and ears. While I did so, there was a

violent burning in my body. Just as if two strong men were to seize a weaker

man by both arms and roast him over a pit of hot coals, so too, while I stopped

the in-breaths and out-breaths through my mouth, nose, and ears, there was a

violent burning in my body. But although tireless energy was aroused in me and

unremitting mindfulness was established, my body was overwrought and strained

because I was exhausted by the painful striving. But such painful feeling that

arose in me did not invade my mind and remain.

“Now when deities saw me, some said: ‘The ascetic Gotama is

dead.’ Other deities said: ‘The ascetic Gotama is not dead, he is dying.’ And

other deities said: ‘The ascetic Gotama is neither dead nor dying; he is an

arahant, for such is the way arahants dwell.’

“I thought: ‘Suppose

I practice entirely cutting off food.’ Then deities came to me and said: ‘Good

sir, do not practice entirely cutting off food. If you do so, we shall infuse

heavenly food into the pores of your skin and this will sustain you.’ I

considered: ‘If I claim to be completely fasting while these deities infuse

heavenly food into the pores of my skin and this sustains me, then I shall be

lying.’ So I dismissed those deities, saying: ‘There is no need.’

“I thought: ‘Suppose

I take very little food, a handful each time, whether of bean soup or lentil

soup or vetch soup or pea soup.’ So I took very little food, a handful each

time, whether of bean soup or lentil soup or vetch soup or pea soup. While I

did so, my body reached a state of extreme emaciation. Because of eating so

little my limbs became like the jointed segments of vine stems or bamboo stems.

Because of eating so little my backside became like a camel’s hoof. Because of

eating so little the projections on my spine stood forth like corded beads.

Because of eating so little my ribs jutted out as gaunt as the crazy rafters of

an old roofless barn. Because of eating so little the gleam of my eyes sank far

down in their sockets, looking like the gleam of water that has sunk far down

in a deep well. Because of eating so little my scalp shriveled and withered as

a green bitter gourd shrivels and withers in the wind and sun. Because of

eating so little my belly skin adhered to my backbone; thus if I touched my

belly skin I encountered my backbone and if I touched my backbone I encountered

my belly skin. Because of eating so little, if I defecated or urinated, I fell

over on my face there. Because of eating so little, if I tried to ease my body

by rubbing my limbs with my hands, the hair, rotted at its roots, fell from my

body as I rubbed.

“Now when people saw

me, some said: ‘The ascetic Gotama is black.’ Other people said: ‘The ascetic

Gotama is not black; he is brown.’ Other people said: ‘The ascetic Gotama is

neither black nor brown; he is golden-skinned.’

So much had the clear, bright color of my skin deteriorated

through eating so little.

“I thought: ‘Whatever

ascetics or brahmins in the past have experienced painful, racking, piercing

feelings due to exertion, this is the utmost; there is none beyond this. And

whatever ascetics and brahmins in the future will experience painful, racking,

piercing feelings due to exertion, this is the utmost; there is none beyond

this. And whatever ascetics and brahmins at present experience painful,

racking, piercing feelings due to exertion, this is the utmost; there is none

beyond this. But by this racking practice of austerities I have not attained

any superhuman distinction in knowledge and vision worthy of the noble ones.

Could there be another path to enlightenment?’

“I considered: ‘I recall

that when my father the Sakyan was occupied, while I was sitting in the cool

shade of a roseapple tree, secluded from sensual pleasures, secluded from

unwholesome states, I entered and dwelled in the first jhāna, which is

accompanied by thought and examination, with rapture and happiness born of

seclusion.18 Could this be the path to enlightenment?’ Then, following on that

memory, came the realization: ‘This is indeed the path to enlightenment.’

“I thought: ‘Why am I

afraid of that happiness that has nothing to do with sensual pleasures and

unwholesome states?’ I thought: ‘I am not afraid of that happiness that has nothing

to do with sensual pleasures and unwholesome states.’

“I considered: ‘It is

not easy to attain that happiness with a body so excessively emaciated. Suppose

I ate some solid food—some boiled rice and porridge.’ And I ate some solid

food—some boiled rice and porridge. Now at that time five monks were waiting

upon me, thinking: ‘If our ascetic Gotama achieves some higher state, he will

inform us.’ But when I ate the boiled rice and porridge, the five monks were

disgusted and left me, thinking: ‘The ascetic Gotama now lives luxuriously; he

has given up his striving and reverted to luxury.’

“Now when I had eaten

solid food and regained my strength, then secluded from sensual pleasures,

secluded from unwholesome states, I entered and dwelled in the first jhāna,

which is accompanied by thought and examination, with rapture and happiness

born of seclusion. But such pleasant feeling that arose in me did not invade my

mind and remain.19

“With the subsiding

of thought and examination, I entered and dwelled in the second jhāna, which

has internal confidence and unification of mind, is without thought and

examination, and has rapture and happiness born of concentration. But such

pleasant feeling that arose in me did not invade my mind and remain.

“With the fading away

as well of rapture, I dwelled equanimous, and mindful and clearly

comprehending, I experienced happiness with the body; I entered and dwelled in

the third jhāna of which the noble ones declare: ‘He is equanimous, mindful, one who dwells happily.’ But such

pleasant feeling that arose in me did not invade my mind and remain.

“With the abandoning

of pleasure and pain, and with the previous passing away of joy and

displeasure, I entered and dwelled in the fourth jhāna, which is neither

painful nor pleasant and includes the purification of mindfulness by

equanimity. But such pleasant feeling that arose in me did not invade my mind

and remain.

“When my mind was

thus concentrated, purified, bright, unblemished, rid of imperfection,

malleable, wieldy, steady, and attained to imperturbability, I directed it to

knowledge of the recollection of past lives. I recollected my manifold past

lives, that is, one birth, two births, three births, four births, five births,

ten births, twenty births, thirty births, forty births, fifty births, a hundred

births, a thousand births, a hundred thousand births, many eons of

world-contraction, many eons of world-expansion, many eons of worldcontraction

and expansion: ‘There I was so named, of such a clan, with such an appearance,

such was my nutriment, such my experience of pleasure and pain, such my

lifespan; and passing away from there, I was reborn elsewhere; and there too I

was so named, of such a clan, with such an appearance, such was my nutriment,

such my experience of pleasure and pain, such my lifespan; and passing away

from there, I was reborn here.’ Thus with their aspects and particulars I

recollected my manifold past lives.

“This was the first

true knowledge attained by me in the first watch of the night. Ignorance was

banished and true knowledge arose, darkness was banished and light arose, as

happens in one who dwells diligent, ardent, and resolute. But such pleasant

feeling that arose in me did not invade my mind and remain.

“When my mind was

thus concentrated, purified, bright, unblemished, rid of imperfection,

malleable, wieldy, steady, and attained to imperturbability, I directed it to

knowledge of the passing away and rebirth of beings. With the divine eye, which

is purified and surpasses the human, I saw beings passing away and being

reborn, inferior and superior, beautiful and ugly, fortunate and unfortunate,

and I understood how beings fare on according to their actions thus: ‘These

beings who behaved wrongly by body, speech, and mind, who reviled the noble

ones, held wrong view, and undertook actions based on wrong view, with the

breakup of the body, after death, have been reborn in a state of misery, in a

bad destination, in the lower world, in hell; but these beings who behaved well

by body, speech, and mind, who did not revile the noble ones, who held right

view, and undertook action based on right view, with the breakup of the body, after

death, have been reborn in a good destination, in a heavenly world.’ Thus with

the divine eye, which is purified and surpasses the human, I saw beings passing

away and being reborn, inferior and superior, beautiful and ugly, fortunate and

unfortunate, and I understood how beings fare on according to their actions.

“This was the second

true knowledge attained by me in the middle watch of the night. Ignorance was

banished and true knowledge arose, darkness was banished and light arose, as

happens in one who dwells diligent, ardent, and resolute. But such pleasant

feeling that arose in me did not invade my mind and remain.

“When my mind was

thus concentrated, purified, bright, unblemished, rid of imperfection,

malleable, wieldy, steady, and attained to imperturbability, I directed it to

knowledge of the destruction of the taints. I directly knew as it actually is:

‘This is suffering. This is the origin of suffering. This is the cessation of

suffering. This is the way leading to the cessation of suffering.’ I directly

knew as it actually is: ‘These are the taints. This is the origin of the

taints. This is the cessation of the taints. This is the way leading to the

cessation of the taints.’

“When I knew and saw

thus, my mind was liberated from the taint of sensual desire, from the taint of

existence, and from the taint of ignorance. When it was liberated, there came

the knowledge: ‘It is liberated.’ I directly knew: ‘Birth is destroyed, the

spiritual life has been lived, what had to be done has been done, there is no

more coming back to any state of being.’

“This was the third

true knowledge attained by me in the last watch of the night. Ignorance was

banished and true knowledge arose, darkness was banished and light arose, as

happens in one who dwells diligent, ardent, and resolute. But such pleasant

feeling that arose in me did not invade my mind and remain.”